science

Des scientifiques ont découvert une communauté microbienne unique sur une ancienne île éphémère

De manière inattendue, les scientifiques ont découvert une population microbienne unique capable de métaboliser le soufre et les gaz atmosphériques, similaire aux micro-organismes détectés dans les évents hydrothermaux en haute mer ou les sources chaudes géothermiques.

Une équipe dirigée par CU Boulder a révélé une communauté microbienne distincte résidant sur l’ancienne île Hunga Tonga de Hunga Ha’apai.

En 2015, un volcan sous-marin du Pacifique Sud est entré en éruption, donnant naissance à l’île éphémère de Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai. L’Université du Colorado à Boulder et le Collaborative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) ont dirigé une équipe de recherche qui a saisi l’opportunité rare d’étudier la population microbienne initiale de la masse continentale récemment formée. Étonnamment, ils ont découvert une population microbienne unique capable de métaboliser le soufre et les gaz atmosphériques, similaire aux organismes trouvés dans les cheminées hydrothermales en haute mer ou les sources chaudes géothermiques.

Ces types d’éruptions volcaniques se produisent partout dans le monde, mais elles ne produisent généralement pas de marées. « Nous avons eu une opportunité incroyablement unique », a déclaré Nick Dragon, PhD, du CIRES. Étudiant et auteur principal d’une étude récemment publiée dans Mbéo. « Personne n’a jamais étudié de manière approfondie les micro-organismes de ce type de système insulaire à un stade aussi précoce. »

« L’étude des microbes qui ont colonisé les premières îles donne un aperçu du stade le plus précoce de l’évolution de l’écosystème, avant l’arrivée des plantes et des animaux », a déclaré Noah Ferrer, boursier CIRES, professeur d’écologie et de biologie évolutive à CU Boulder et auteur correspondant de l’étude. .

Une équipe multi-institutionnelle de chercheurs sur le terrain a collecté des échantillons de sol de l’île, puis les a expédiés au campus de l’Université du Colorado à Boulder. Dragone et Fierer peuvent ensuite être extraits et séquencés[{ » attribute= » »>DNA samples from the samples.

“We didn’t see what we were expecting,” said Dragone. “We thought we’d see organisms you find when a glacier retreats, or cyanobacteria, more typical early colonizer species—but instead we found a unique group of bacteria that metabolize sulfur and atmospheric gases.”

And that wasn’t the only unexpected twist in this work: On January 15, 2022, seven years after it formed, the volcano erupted again, obliterating the entire landmass in the largest volcanic explosion of the 21st century. The eruption completely wiped out the island and eliminated the option for the team to continue monitoring their site.

“We were all expecting the island to stay,” said Dragone. “In fact, the week before the island exploded we were starting to plan a return trip.”

However, the same fickle nature of the Hunga Tonga Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) that made it explode also explains why the team found such a unique set of microbes on the island. Hunga Tonga was volcanically formed, like Hawaii.

“One of the reasons why we think we see these unique microbes is because of the properties associated with volcanic eruptions: lots of sulfur and hydrogen sulfide gas, which are likely fueling the unique taxa we found,” Dragone said. “The microbes were most similar to those found in hydrothermal vents, hot springs like Yellowstone, and other volcanic systems. Our best guess is the microbes came from those types of sources.”

The expedition to HTHH required close collaboration with members of the government of the Kingdom of Tonga, who were willing to work with researchers to collect samples from land normally not visited by international guests. Coordination took years of work by collaborators at the Sea Education Association and NASA: a Tongan observer must approve and oversee any sample collection that takes place within the Kingdom.

“This work brought in so many people from around the world, and we learned so much. We are of course disappointed that the island is gone, but now we have a lot of predictions about what happens when islands form,” said Dragone. “So if something formed again, we would love to go there and collect more data. We would have a game plan of how to study it.”

Reference: “The Early Microbial Colonizers of a Short-Lived Volcanic Island in the Kingdom of Tonga” by Nicholas B. Dragone, Kerry Whittaker, Olivia M. Lord, Emily A. Burke, Helen Dufel, Emily Hite, Farley Miller, Gabrielle Page, Dan Slayback and Noah Fierer, 11 January 2023, mBio.

DOI: 10.1128/mbio.03313-22

« Spécialiste de la télévision sans vergogne. Pionnier des zombies inconditionnels. Résolveur de problèmes d’une humilité exaspérante. »

science

Des astronomes ont découvert des « embouteillages » de trous noirs dans les centres galactiques

Couple normal individuel de M• = 107M⊙ problème. Les lignes noires montrent le couple de type I ainsi que le couple GW. Les lignes violettes représentent le couple thermique, tandis que les lignes bleues représentent le couple total. Panneau de gauche : couple tracé dans l’espace R. Panneau de droite : couple tracé dans l’espace τ. Les lignes verticales pointillées indiquent τ± (vert) et τ0 (rouge), endroits où des pièges migratoires sont susceptibles de se produire. crédit: Avis mensuels de la Royal Astronomical Society (2024). est ce que je: 10.1093/mnras/stae828

× Fermer

Couple normal individuel de M• = 107M⊙ problème. Les lignes noires montrent le couple de type I ainsi que le couple GW. Les lignes violettes représentent le couple thermique, tandis que les lignes bleues représentent le couple total. Panneau de gauche : couple tracé dans l’espace R. Panneau de droite : couple tracé dans l’espace τ. Les lignes verticales pointillées indiquent τ± (vert) et τ0 (rouge), endroits où des pièges migratoires sont susceptibles de se produire. crédit: Avis mensuels de la Royal Astronomical Society (2024). est ce que je: 10.1093/mnras/stae828

Une étude internationale, dirigée par des chercheurs de l'Université Monash, a révélé des informations importantes sur la dynamique des trous noirs au sein des disques massifs situés au centre des galaxies.

Publié dans Avis mensuels de la Royal Astronomical Society, l'étude Il montre les processus complexes qui déterminent quand et où les trous noirs ralentissent et interagissent les uns avec les autres, conduisant potentiellement à des fusions.

Les résultats de l’étude mettent en évidence les émissions d’ondes gravitationnelles (GW) provenant de la fusion des trous noirs, événements qui peuvent être détectés par des instruments tels que le Laser Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO).

Lorsque deux trous noirs se rapprochent trop, ils perturbent l’espace-temps lui-même, émettant des ondes gravitationnelles avant de finalement fusionner en un seul trou.

Le Dr Evgeny Grishin, chercheur postdoctoral à l'École de physique et d'astronomie de l'Université Monash qui a dirigé l'étude, a comparé le phénomène à une intersection très fréquentée sans feux de signalisation fonctionnels.

« Nous avons examiné combien et où nous aurions ces intersections très fréquentées », a déclaré le Dr Grishin.

La recherche s'est concentrée sur les centres des galaxies, où les trous noirs peuvent fusionner plusieurs fois en raison de l'énorme force gravitationnelle du trou noir supermassif situé au centre.

De plus, la présence d’un disque d’accrétion massif de gaz contribue à la luminosité de ces galaxies, les classant parmi les noyaux galactiques actifs (AGN).

L'interaction entre les trous noirs plus petits et le gaz environnant les fait migrer à l'intérieur du disque, s'accumulant dans des régions appelées pièges à migration. Ces pièges augmentent la possibilité de collisions rapprochées entre trous noirs, pouvant conduire à des fusions.

« Les effets thermiques jouent un rôle crucial dans ce processus, affectant l'emplacement et la stabilité des pièges migratoires. Cela implique notamment que nous ne voyons pas de pièges migratoires se produire dans les galaxies actives à grande luminosité », a déclaré le Dr Grishin.

Les résultats de l’étude font progresser notre compréhension des fusions de trous noirs et ont des implications plus larges pour l’astronomie des ondes gravitationnelles, l’astrophysique des hautes énergies, l’évolution des galaxies et la rétroaction des noyaux galactiques actifs.

« Malgré ces découvertes importantes, beaucoup de choses sur la physique des trous noirs et de leurs environnements restent inconnues », a déclaré le Dr Grishin. « Nous sommes satisfaits des résultats et nous sommes désormais sur le point de découvrir où et comment les trous noirs fusionnent dans les noyaux galactiques.

« L’avenir de l’astronomie des ondes gravitationnelles et de la recherche sur les noyaux galactiques actifs est exceptionnellement prometteur. »

Plus d'information:

Evgeny Grishin et al., Effet du couple thermique sur les pièges de migration des disques AGN et les amas d'ondes gravitationnelles, Avis mensuels de la Royal Astronomical Society (2024). est ce que je: 10.1093/mnras/stae828

Informations sur les magazines :

Avis mensuels de la Royal Astronomical Society

« Spécialiste de la télévision sans vergogne. Pionnier des zombies inconditionnels. Résolveur de problèmes d’une humilité exaspérante. »

science

La fusée Falcon 9 de SpaceX vient de terminer une mission historique

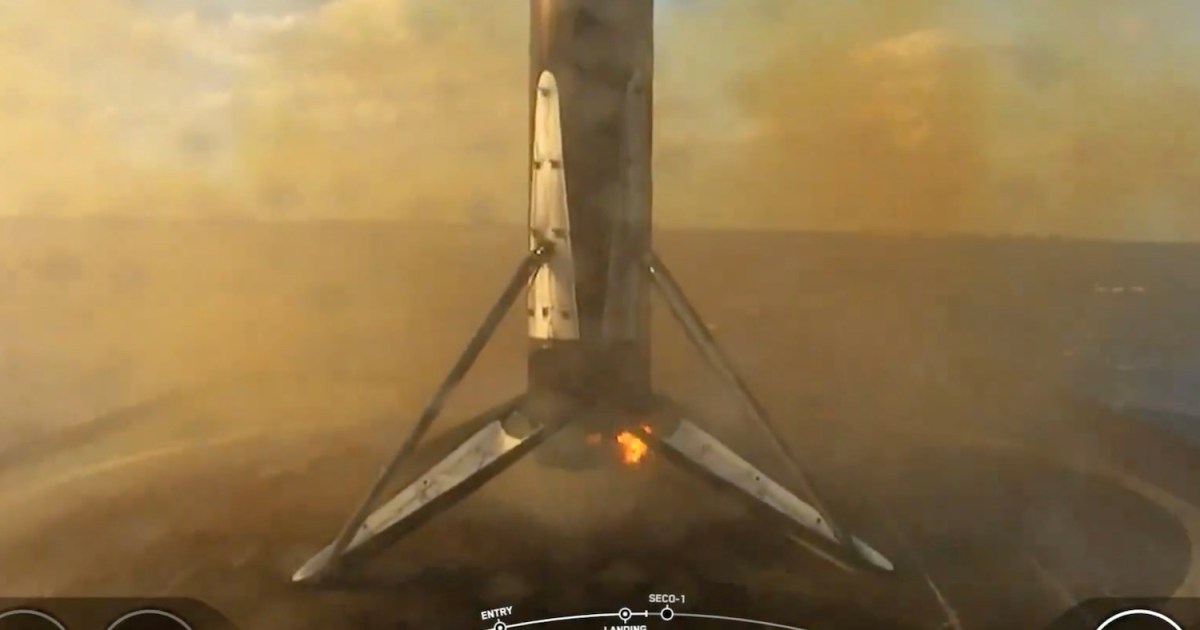

SpaceX lance et fait atterrir des fusées depuis 2015, même si certains de ces premiers atterrissages ne se sont pas déroulés comme prévu et se sont soldés par une boule de feu.

De nos jours, les atterrissages sont en grande partie terminés et mardi soir, la compagnie de vols spatiaux a réussi son 300e atterrissage réussi de première étape. Elon Musk, PDG de SpaceX Il a félicité son équipe Pour réaliser cet exploit.

La mission de mardi visant à déployer 23 satellites Starlink en orbite a décollé du Kennedy Space Center en Floride à 18 h 17 HE. SpaceX a diffusé en direct la mission historique sur les réseaux sociaux :

Moteurs à pleine puissance et décollage ! pic.twitter.com/FeW78mZio2

– EspaceX (@SpaceX) 23 avril 2024

Environ huit minutes après le lancement, le premier étage de la fusée Falcon 9 a effectué un atterrissage droit parfait à bord du drone Just Read the Instructions stationné dans l'océan Atlantique. Regardez le booster de 41,2 mètres effectuer le 300ème atterrissage du booster Falcon 9 :

Le premier étage du Falcon 9 a atterri sur le drone Just Read the Instructions, complétant ainsi le 300ème atterrissage du Falcon ! pic.twitter.com/1YHqiHWjkN

– EspaceX (@SpaceX) 23 avril 2024

L'atterrissage du premier étage du booster de cette manière permet à SpaceX d'effectuer des missions à un coût bien inférieur à celui s'il devait construire une nouvelle mission pour chaque vol. Il est également devenu possible d'obtenir une fréquence de tir plus élevée. La société a construit plusieurs boosters Falcon 9 qui ont volé plusieurs fois au fil des ans. La mission de mardi était le neuvième vol de cette fusée particulière, qui a déjà lancé Crew-6, SES O3b mPOWER, USSF-124 et maintenant six missions Starlink.

Le record de vol actuel détenu par une seule fusée SpaceX appartient à Booster 1062, qui a été lancé et atterri plus tôt ce mois-ci pour une 20e fois record.

SpaceX a réalisé son premier atterrissage d'appoint en 2015 après avoir connu un certain nombre d'accidents au cours desquels le véhicule a atterri avec trop de force ou est tombé après l'atterrissage. L’équipe a atteint 200 atterrissages en juin dernier, et comme SpaceX augmente régulièrement son taux de lancement, le 400e atterrissage aura probablement lieu encore plus rapidement.

Recommandations des rédacteurs

« Spécialiste de la télévision sans vergogne. Pionnier des zombies inconditionnels. Résolveur de problèmes d’une humilité exaspérante. »

science

La sonde spatiale Voyager 1 transmet à nouveau des données après que la NASA les a détectées à distance à 24 milliards de kilomètres – The Irish Times

:quality(70):focal(955x387:965x397)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/F25H742JEFAG6EW6JFDXDFWGZQ.jpg)

Le vaisseau spatial le plus éloigné de la Terre, Voyager 1, a recommencé à communiquer correctement avec la NASA après que les ingénieurs ont travaillé pendant des mois pour réparer à distance la sonde vieille de 46 ans.

Le Jet Propulsion Laboratory de la NASA, qui construit et exploite le vaisseau spatial robotique de l'agence, a déclaré en décembre que la sonde, située à plus de 24 milliards de kilomètres, envoyait un code absurde à la Terre.

Dans une mise à jour publiée lundi, le JPL a annoncé que l’équipe de la mission avait pu « après quelques investigations innovantes » obtenir des données utilisables sur la santé et l’état des systèmes d’ingénierie de Voyager 1. « La prochaine étape consiste à permettre au vaisseau spatial de commencer à apporter les données scientifiques. dos. » Elle a ajouté que malgré le défaut, Voyager 1 fonctionnait normalement depuis le début.

Lancé en 1977, Voyager 1 a été conçu dans le but principal d'effectuer des études rapprochées de Jupiter et de Saturne au cours d'une mission de cinq ans. Cependant, son voyage s'est poursuivi et le vaisseau spatial approche désormais d'un demi-siècle d'exploitation.

Voyager 1 a pénétré dans l'espace interstellaire en août 2012, ce qui en fait le premier objet fabriqué par l'homme à quitter le système solaire. Il roule actuellement à une vitesse de 60 821 km/h.

Le dernier problème était lié à l'un des trois ordinateurs à bord du vaisseau spatial, chargé de remplir les données scientifiques et techniques avant de les envoyer sur Terre. Incapable de réparer une puce cassée, l'équipe du JPL a décidé de déplacer le code endommagé ailleurs, une tâche difficile compte tenu de la technologie obsolète.

Les ordinateurs de Voyager 1 et de sa sœur Voyager 2 disposaient de moins de 70 kilo-octets de mémoire au total, soit l'équivalent d'une image informatique à basse résolution. Ils utilisent de vieilles bandes numériques pour enregistrer des données.

La réparation a été envoyée depuis la Terre le 18 avril, mais il a fallu deux jours pour évaluer si elle a réussi, car il faut environ 22 heures et demie pour que le signal radio atteigne Voyager 1 et 22 heures supplémentaires pour que la réponse revienne sur Terre. .

« Lorsque l'équipe de vol de la mission a reçu une réponse du vaisseau spatial le 20 avril, elle a constaté que la modification fonctionnait », a déclaré le JPL.

Parallèlement à son annonce, le JPL a publié une photo des membres de l'équipe de vol du Voyager applaudissant et applaudissant dans une salle de conférence après avoir reçu des données utilisables, avec des ordinateurs portables, des cahiers et des cookies sur la table devant eux.

L'astronaute canadien à la retraite Chris Hadfield, qui a participé à deux missions de navette spatiale et a servi comme commandant de la Station spatiale internationale, a comparé la mission du JPL à l'entretien longue distance d'une vieille voiture.

« Imaginez qu'une puce informatique se brise dans votre voiture en 1977. « Imaginez maintenant qu'elle se trouve dans l'espace interstellaire, à 25 milliards de kilomètres de là », a écrit Hadfield.

Voyager 1 et 2 ont fait de nombreuses découvertes scientifiques, notamment des enregistrements détaillés de Saturne et la révélation que Jupiter possède également des anneaux, ainsi qu'une activité volcanique active sur l'une de ses lunes, Io. Des sondes ont ensuite découvert 23 nouvelles lunes autour des planètes extérieures.

Parce que leur trajectoire les éloigne du Soleil, les sondes du Voyager sont incapables d'utiliser des panneaux solaires et convertissent à la place la chaleur générée par la désintégration radioactive naturelle du plutonium en électricité pour alimenter les systèmes du vaisseau spatial.

La NASA espère continuer à collecter des données des deux vaisseaux spatiaux Voyager pendant encore plusieurs années, mais les ingénieurs s'attendent à ce que les sondes soient trop hors de portée pour communiquer d'ici une décennie environ, en fonction de la quantité d'énergie qu'elles peuvent générer. Voyager 2 est un peu en retard sur son jumeau et se déplace un peu plus lentement.

Dans environ 40 000 ans, les deux sondes passeront relativement près, en termes astronomiques, de deux étoiles. Voyager 1 s'approchera à moins de 1,7 années-lumière d'une étoile de la constellation de la Petite Ourse, tandis que Voyager 2 s'approchera à une distance similaire d'une étoile appelée Ross 248 dans la constellation d'Andromède. -Gardien

« Spécialiste de la télévision sans vergogne. Pionnier des zombies inconditionnels. Résolveur de problèmes d’une humilité exaspérante. »

-

entertainment2 ans ago

Découvrez les tendances homme de l’été 2022

-

Top News2 ans ago

Festival international du film de Melbourne 2022

-

Tech1 an ago

Voici comment Microsoft espère injecter ChatGPT dans toutes vos applications et bots via Azure • The Register

-

science2 ans ago

Les météorites qui composent la Terre se sont peut-être formées dans le système solaire externe

-

science3 ans ago

Écoutez le « son » d’un vaisseau spatial survolant Vénus

-

Tech2 ans ago

F-Zero X arrive sur Nintendo Switch Online avec le multijoueur en ligne • Eurogamer.net

-

entertainment1 an ago

Seven révèle son premier aperçu du 1% Club

-

entertainment1 an ago

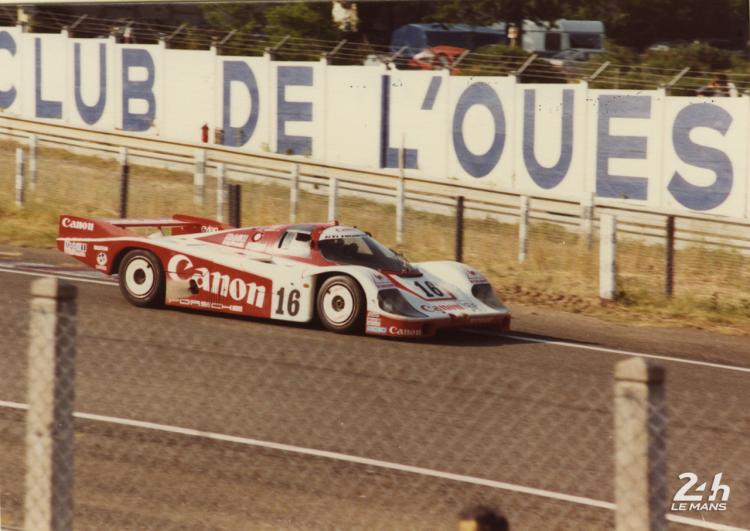

Centenaire des 24 Heures – La musique live fournit une bande-son pour la course